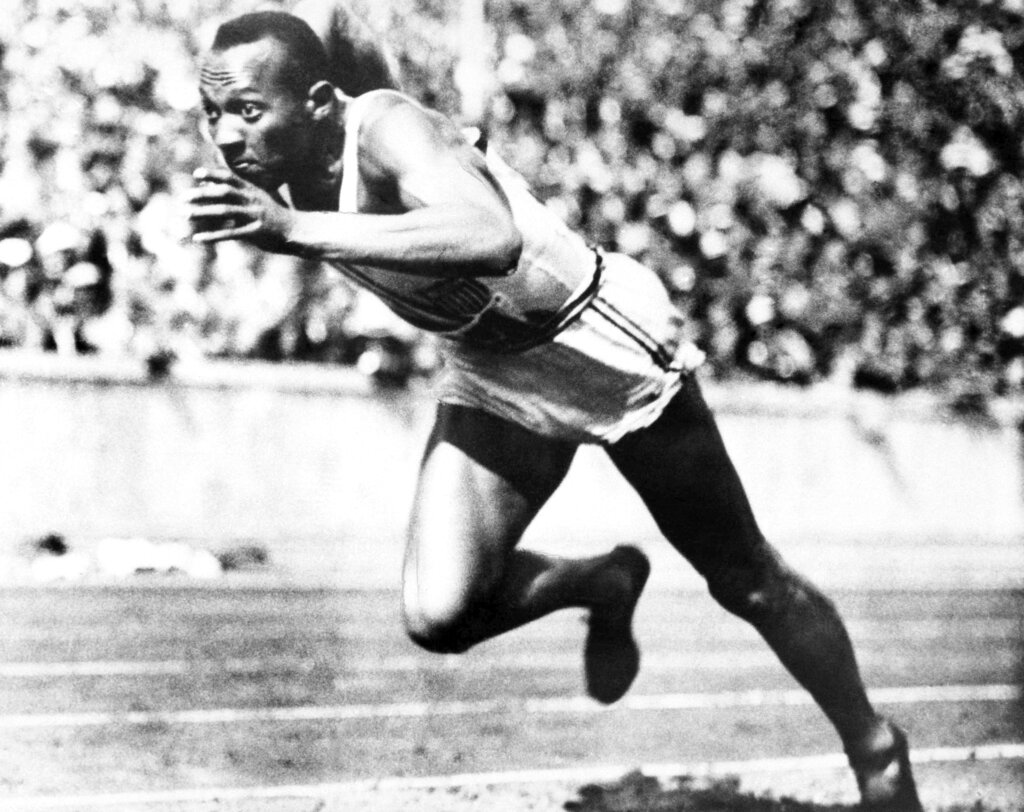

Jesse Owens attempted to block everything out — from the chants of the German crowd to the glares of Adolf Hitler in a seat looking down.

As legend goes, there was one thing the American great heard loud and clear: Advice from an unlikely ally.

Owens was a Black athlete at the 1936 Berlin Games who stole the show by winning four gold medals and dispelling the Nazi claims of Aryan supremacy.

In the long jump he received an assist from a German named Carl Ludwig “Luz” Long. A technical tip from his rival allowed Owens to leap to victory inside a stadium built by Hitler as a celebration of the Third Reich.

It started a friendship between Owens and Long so dear that generations later, their families remain close.

Their bond transcended race relations, with the two even walking arm-in-arm from the awards ceremony. There was Owens, the son of an Alabama sharecropper and Long, the blonde-haired, blue-eyed German, celebrating under the ever-looming presence of Hitler.

“More than the hate of Hitler, there's the friendship of Owens and Long. Now that’s something that can truly inspire,” Owens' granddaughter Marlene Dortch said. “The times take you into a scenario that has nothing to do with what you’re thinking but results in something bigger than the moment.”

Owens was off to a quick start in Berlin as he took gold in the 100 meters by edging Ralph Metcalfe, another standout African American athlete, with Hitler looking on.

The next day featured the long jump and Owens found himself in danger of not making it out of the qualifying round. He was down to his final jump.

Then, a calming voice: Take off farther from the foul line.

It was Long. Owens heeded his opponent's words and went on to win his second gold — in a back-and-forth contest with Long, who wound up with silver.

The first to congratulate Owens was his German rival. Despite the political undertones, he and Owens walked from the stadium arm-in-arm.

“Luz knew there were going to be some repercussions. He didn’t care,” said Dortch, whose grandfather also won gold in the 200 meters and another as part of the 4x100 relay. “That was an authentic moment.”

There’s been some debate about what Long actually said — if anything — to ease Owens' mind.

Regardless, it doesn’t change this: A bond was forged.

Owens wouldn't see his new friend in person again after the Olympics.

Long fought for Germany during World War II and was killed in action in 1943. Before his death, Long reportedly wrote a letter to Owens and asked him to tell Long's son, Kai, about what times can be like between people when there's no war.

Owens honored the request in a visit. The families have remained in contact.

Throughout his life, Owens was a popular figure in Berlin with German school kids sending him letters.

Soon after his death in 1980 of lung cancer, Owens was honored by the city of Berlin with a street named in his honor. It runs in front of the historic stadium where he along with 17 other African-Americans competed under the gaze of Hitler. They earned a combined 14 medals.

Things weren't always easy for Owens back home after the Olympics. There was a parade for the sprinter nicknamed the “Buckeye Bullet” for his exploits at Ohio State. But there was no visit to the White House.

And despite his fame, Owens was ushered into many hotels through the kitchen entrance and up the service elevator.

“The myth is that Jesse Owens and other Black athletes just overturned this idea of white supremacy with their performances. It would be great if that had been the case,” said David Clay Large, author of the “ Nazi Games: The Olympics of 1936.”

His amateur status was revoked for wanting to pursue more lucrative deals. Owens tried to make a living any way he could for his wife and three daughters. He started a dry cleaning business and served as a gas station attendant. He also raced against horses and even cars for extra cash. Later, he made a career out of public appearances and delivering speeches.

In 1990, President George H.W. Bush posthumously awarded Owens the Congressional Gold Medal for his achievements.

In 2016, another generation was introduced to Owens through “Race,” a movie based on his life.

“The one thing I learned during the promotion of ‘Race’ was how many young people didn’t know much about him, and wanted to learn more after seeing the movie,” Owens’ granddaughter Gina Hemphill Strachan said. "He's inspired so many. He continues to inspire."

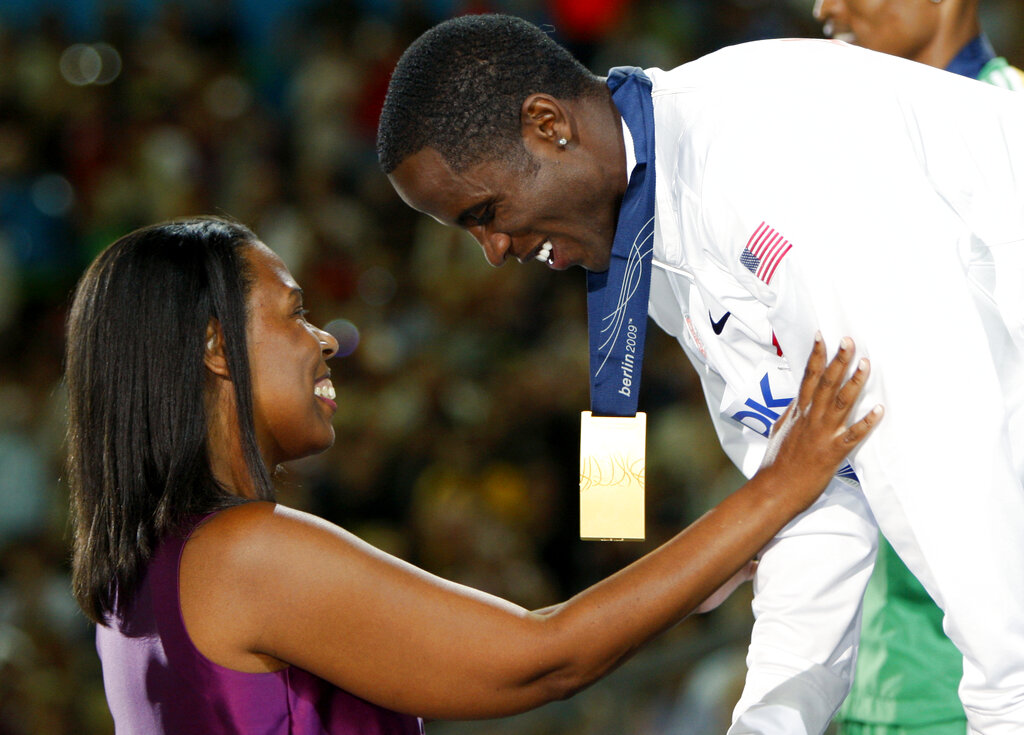

Dortch went back to the Berlin stadium for the world track and field championships in 2009. She stepped into the box where Hitler once looked down on the track. With her that day were members of the Long family.

It was a powerful moment.

“When I think of my grandfather, I think of determination and grit and of a man whose story in 1936 is just as relevant today,” Dortch said. "A legacy is what he left us. Not just with his gold medals, and as a great athlete and a great American, but also as a great human being.”