RIVERSIDE, Ca. (AP) — Greg Laurie is among America’s most successful clergymen -- senior pastor at a California megachurch, prolific author, host of a global radio program. Yet after a youthful colleague’s suicide, his view of his vocation is unsparing.

“Pastors are people, just like everyone else,” Laurie said by email. “We are broken people who live in a broken world. Sometimes, we need help too.”

Laurie’s 15,000-member Harvest Christian Fellowship, based in Riverside, California, was jolted in September by the death of Jarrid Wilson, a 30-year-old associate pastor. Wilson and his wife, parents of two sons, had founded an outreach group to help people coping with depression and suicidal thoughts.

"People may think that as pastors or spiritual leaders we are somehow above the pain and struggles of everyday people," Laurie wrote after Wilson’s death. "We are the ones who are supposed to have all the answers. But we do not."

“I know what depression is,” he said. “You?have to?sit?in your car when you drive up in the driveway of the church?and get your game face on to go in there.?I have contemplated walking away so many times.” - Pastor Rodney McNeal

There is similar introspection among clergy of many faiths across the United States as the age-old challenges of their ministries are deepened by a host of newly evolving stresses. Rabbis worry about protecting their congregations from anti-Semitic violence. A shortage of Catholic priests creates burdens for those who remain. Worries for Protestant pastors range from crime and drug addiction in their communities to financial insecurity for their own families to social media invective that targets them personally.

Adam Hertzman, who works for the Jewish Federation of Pittsburgh, witnessed firsthand the emotional toll on his city’s rabbis after the October 2018 massacre that killed 11 Jews at the Tree of Life synagogue.

“Somehow in the U.S. we expect our clergy to be superhuman when it comes to these things, and frankly that’s an unrealistic expectation,” he said. “They’re human beings who are going to feel the same kind of fear and numbness and depression that other people do.”

What keeps him going? “I love seeing people just turn their lives around,” he said. “I will be out in the community and somebody will say ‘Hey man, you changed my life. You helped me.’” - Pastor Rodney McNeal

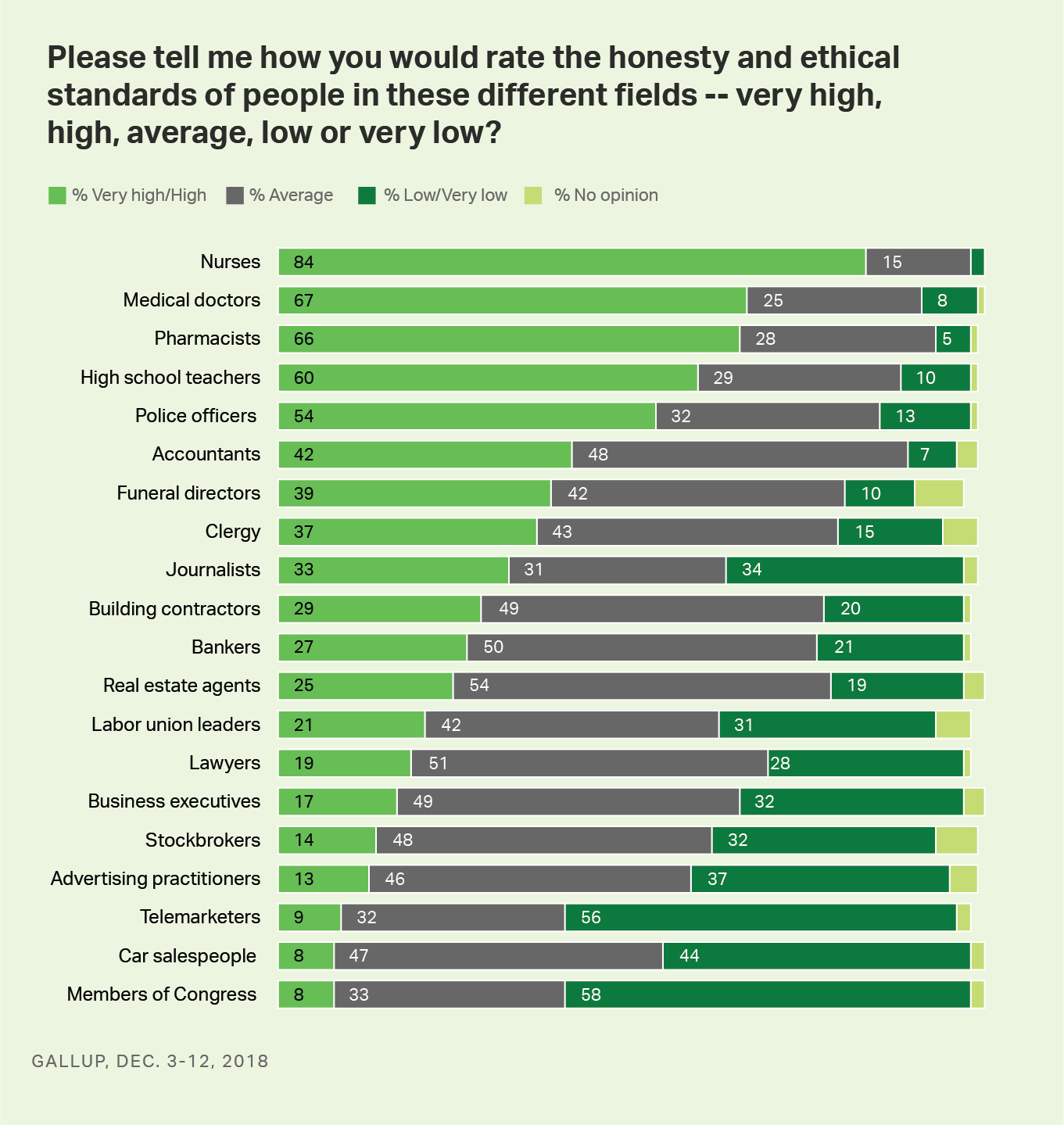

It’s difficult to quantify the extent of clergy stress, nationwide or denominationally. But a 2018 Gallup poll bears out a widely shared impression that clergy no longer enjoy the same public esteem as in the past. Only 37% of American rate members of the clergy highly for their honesty and ethics, the lowest rating in the 40 years Gallup has asked that question.

“Not very long ago, they were seen as one of the pillars of the community,” said Carl Weisner, senior director of Duke Divinity School’s Clergy Health Initiative. “There has been some loss of status... and that does add to stress.”

Yet Weisner says the challenges of ministry are often offset by the rewards.

“There’s a gift of meaning in the work that not a whole lot of other professions have,” he said.

Stress — and rewards — come in many forms for Rodney McNeal, 54, an Army veteran and hospital?social worker?who has pastored Second?Bethlehem Baptist Church?in Alexandria, Louisiana for nearly eight years.

Officially, the African American church has 300 members but only about 130 attend a typical service, he said.

“They don’t understand that I get tired like they get tired," he said. “They want you to be at their constant beck and call.”

He has attended five seminaries but never completed them. The courses, he said, didn’t cover the things he sees on the job.

“The preaching part is the easy part,” he said. “Had?I known the ugly side of ministry -- the hospital visits, burying the dead, being in the room when someone is dying?and trying to comfort their family... Had I known?all that,?I don’t think I would have accepted being a pastor.”

When he began, McNeal?rarely took time off, straining his marriage.

Although he has tried to create a work-life balance, he visits sick congregants on his lunch break and, if he gets off his job at 4:30 p.m.,?tries to make two or three home and hospital visits before he picks up his children at school.

McNeal said pastors in small congregations get close to their parishioners; when a tragedy strikes, “you are feeling?the same?pains.”

“You?have to?get them through the?process,?but nobody is there to help?you,” he said.

Over the years McNeal has?opened up?to two older pastors who counsel him. He also talks to his brother, who is a minister in?North Carolina.

“I know what depression is,” he said. “You?have to?sit?in your car when you drive up in the driveway of the church?and get your game face on to go in there.?I have contemplated walking away so many times.”

What keeps him going?

“I love seeing people just turn their lives around,” he said. “I will be out in the community and somebody will say ‘Hey man, you changed my life. You helped me.’”

In Baltimore, the Rev. Alvin Gwynn -- at age 74 -- has been getting help from computer-savvy millennials as he serves for a 30th year as pastor of Friendship Baptist Church. His mostly African American congregation of 1,100 is flourishing, he says, and yet he’s weighed down sometimes by the multiple crises of his city -- high crime and drug abuse, underfunded schools, a lack of decent affordable housing.

“The hardest thing is trying to keep people’s hope alive,” he said. “We’re no longer a friendly city -- our families have been torn apart, and people don’t have the interaction with the church that they once had.”

The National Association of Evangelicals, which represents more than 45,000 churches in the U.S., published research in 2016 detailing pervasive financial stress among its pastors. Of more than 4,200 pastors surveyed, half earned less than $50,000 a year and more than 90% worried about insufficient retirement savings. Only 20% said their congregations had more than 200 people.

Yet pastors in booming megachurches can suffer as well. Jarrid Wilson’s death in September was preceded in August 2018 by the suicide of Andrew Stoecklein, the 30-year-old pastor of Inland Hills Church in Chino, California. A few days before killing himself, Stoecklein had preached about his own struggles with panic attacks and depression.

Wilson’s suicide was among the reasons that megachurch pastor Howard John Wesley recently told his 10,000-member congregation at Alfred Street Baptist Church in Alexandria, Virginia, that he was taking a 15-week sabbatical.

"There's not been a day in these past 11 years that I have not woken up and knew that there's something I had to do for the church, that I have to be available for a call,” Wesley said. “I’m tired.”