Hospitals across the U.S. are feeling the wrath of the omicron variant and getting thrown into disarray that is different from earlier COVID-19 surges.

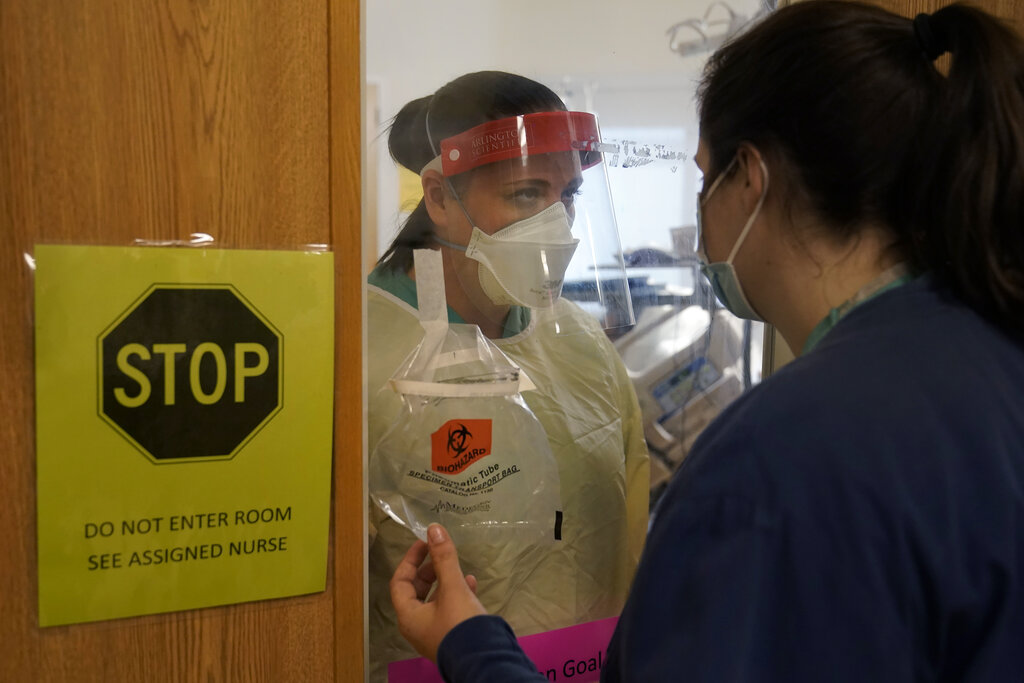

This time, they are dealing with serious staff shortages because so many health care workers are getting sick with the fast-spreading variant. People are showing up at emergency rooms in large numbers in hopes of getting tested for COVID-19, putting more strain on the system. And a surprising share of patients — two-thirds in some places — are testing positive for the virus while in the hospital for other reasons.

At the same time, hospitals say the patients aren’t as sick as those who came in during the last surge. Intensive care units aren’t as full, and ventilators aren’t needed as much as they were before.

The pressures are neverthless prompting hospitals to scale back non-emergency surgeries and close wards, while National Guard troops have been sent in in several states to help out at medical centers and testing sites.

Nearly two years into the pandemic, frustration and exhaustion are running high among health care workers.

“This is getting very tiring, and I’m being very polite in saying that,” said Dr. Robert Glasgow of University of Utah Health, which has hundreds of workers out sick or in isolation.

About 85,000 Americans are in the hospital with COVID-19, just short of the delta-surge peak of about 94,000 in early September, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The all-time high during the pandemic was about 125,000 in January of last year.

But the hospitalization numbers do not tell the full story. At least some cases in the official count involve mild or symptom-free infections that weren't what put the patients in the hospital in the first place.

Dr. Fritz François, chief of hospital operations at NYU Langone Health in New York City, said about 65% of patients admitted to that system with COVID-19 recently were primarily hospitalized for something else and were incidentally found to have the virus.

Joanne Spetz, associate director of research at the Healthforce Center at the University of California, San Francisco, said the rising number of cases like that is both good and bad.

The lack of symptoms shows vaccines, boosters and natural immunity from prior infections are working, she said. The bad news is that the numbers mean the coronavirus is spreading rapidly, and some percentage of those people will wind up needing hospitalization.

This week, 36% of California hospitals reported critical staffing shortages. And 40% are expecting such shortages.

Some hospitals are reporting as much as one quarter of their staff out for virus-related reasons, said Kiyomi Burchill, the California Hospital Association’s vice president for policy and leader on pandemic matters.

In response, hospitals are turning to temporary staffing agencies or transferring patients out.

University of Utah Health plans to keep more than 50 beds open because it doesn't have enough nurses. It is also rescheduling surgeries that aren’t urgent. In Florida, a hospital temporarily closed its maternity ward because of staff shortages.

As of Monday, New York state had just over 10,000 people in the hospital with COVID-19, including 5,500 in New York City. That’s the most in either the city or state since the disastrous spring of 2020.

New York City hospital officials, though, reported that things haven’t become dire. Generally, the patients aren’t as sick as they were back then. Of the patients hospitalized in New York City, around 600 were in ICU beds, which is only a few more than were in intensive care on this date last winter.

“We’re not even halfway to what we were in April 2020,” said Dr. David Battinelli, the physician-in-chief for Northwell Health, New York state’s largest hospital system.

Amid the omicron-triggered surge in demand for COVID-19 testing across the U.S., New York City's Fire Department is asking people not to call for ambulance simply because they are having trouble finding a test.

In Ohio, Gov. Mike DeWine announced new or expanded testing sites in nine cities to redirect test-seekers away from ERs. About 300 National Guard members are being sent to help out at those centers.

In Connecticut, many ER patients are in overflow beds in hallways, and nurses are often working double shifts because of staffing shortages, said Sherri Dayton, a nurse at the Backus Plainfield Emergency Care Center. Many emergency rooms have hours-long waiting times, she said.

“We are drowning. We are exhausted,” Dayton said.

Doctors and nurses complain about burnout and a sense their neighbors are no longer treating the pandemic as a crisis, despite day after day of record COVID-19 cases.

“In the past, we didn’t have the vaccine, so it was us all hands together, all the support. But that support has kind of dwindled from the community, and people seem to be moving on without us,” said Rachel Chamberlin, a 26-year-old nurse at New Hampshire's Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center.

Edward Merrens, chief clinical officer at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health, said more than 85% of the hospitalized COVID-19 patients were unvaccinated.

Several COVID-19 patients in the hospital's COVID-19 ICU unit were on ventilators, a breathing tube down their throats. In one room, staff members made preparations for what they feared would be the final family visit for a dying patient.

One of the unvaccinated was Fred Rutherford, a 55-year-old from Claremont, New Hampshire. He son carried him out of the house when he became sick and took him to the hospital, where he needed a breathing tube for a while and feared he might die.

If he returns home, he said, he promises to get vaccinated and tell others to do so, too.

“I probably thought I was immortal, that I was tough,” Rutherford said, speaking from his hospital bed behind a window, his voice weak and shaky.

But he added: "I will do anything I can to be the voice of people that don’t understand you’ve got to get vaccinated. You’ve got to get it done to protect each other."

___

Casey reported from Boston and Thompson from Sacramento. Associated Press writers Terry Tang and Bobby Calvan in New York City contributed to this report.